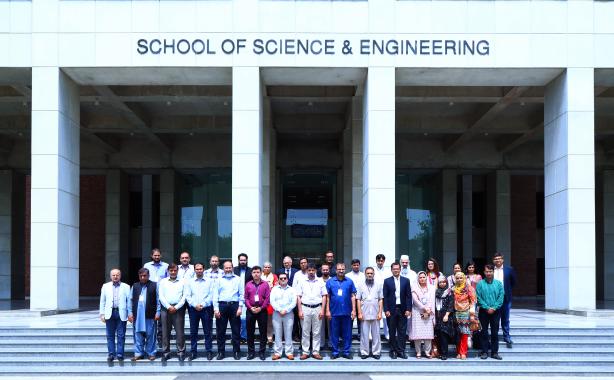

The Syed Babar Ali School of Science and Engineering (SBASSE) at LUMS concluded a 3-day workshop titled 'Leaders in Science and Innovation Policy.' The workshop was attended by 30+ senior leaders from the academia, government sector and public labs; these included Vice Chancellors, Professors, Heads of ORICs, Scientists and government bureaucrats engaged in scientific advice.

The workshop was led by Mr. Ehsan Masood, Knight Science Journalism Fellow at MIT and a former Editor of the prestigious science journal Nature in the United Kingdom and Dr. Athar Osama, Member of Science and Technology at the Planning Commission who is a recognised authority on Science in the Muslim World. He is a Fellow of the World Technology Network (WTN) and a Young Global Leader of the World Economic Forum. Dr. Suleman Shahid from the Department of Computer Science at SBASSE was the Programme Lead from LUMS.

The workshop covered a range of different subjects and topics of interest to senior leaders in science and innovation policy, such as history and evolution of science policy around the world, science policymaking processes, scientific advice, commercialisation and impact, measurement of science, and scientific ethics, among others.

Dr. Tariq Banuri, Chairman, Higher Education Commission, in his keynote speech at the workshop, laid out the conditions and requirements of making science more relevant to policy and how to address the trust deficit between the policymaker and the scientific community. He advised the participants it was perfectly normal for a vast majority of the scientists to remain engaged in the realm of science only, but those who sought policy impact need to work hard and get out of their comfort zones to do so.

The participants learnt from history and policy elsewhere and discussed how to leverage and adapt these ideas to the Pakistani policy setting. They had vigorous debates on these issues and devised some recommendations for policymakers in both areas of Higher Education and the Science and Technology to help enhance the productivity and effectiveness of the country's S&T eco-system.

Speaking earlier, Dr. Athar Osama noted that the S&T capability of a country can be thought of as a chair with four legs to stand on; these legs include the public S&T system, the academia or higher education system, the defense S&T establishment, and the private sector. Each must play its part for the overall system to deliver results. In Pakistan's case, he said, the chair is standing on drastically unequal legs with the private sector leg almost missing from the equation and public sector leg being deprived of nourishment since the late 1980s. No wonder then that the country is unable to develop a robust and impactful science and technology eco-system.

Ehsan Masood who has covered Pakistan for Nature for well over two decades, hoped that the new government will take necessary measures to revive S&T in Pakistan, correct the aberrations (e.g. neglect of public labs and revival of NCST) and make it a central part of a strategy of economic revival and export competitiveness.

Over the 3 days, the participants were exposed to a range of different ideas through lectures, groups discussions, and invited talks. The participants also carried out a number of exercises such as deciding grand national challenges for science and arriving at a consensus on what universities should or should not do.

The workshop was the first of its kind in Pakistan and could be a model for capacity building and developing a shared understanding of critical issues for senior leaders in science and academia.